This article first appeared in the Broomfield Enterprise.

One largely forgotten name from the early days of the Denver-Boulder area is the town of Globeville. Today a Denver neighborhood located just north of the tangled intersection of I-70 and I-25 (the “mousetrap”), Globeville was once a thriving town in its own right — with a very rowdy history.

Settled in the late 1880s, mostly by eastern European immigrants, Globeville offered jobs at gold and silver smelting plants and other labor-intensive industries. Unhappily subject to periodic floods from the nearby South Platte River, the town developed a unique character early on because of its physical and cultural isolation from Denver and other neighboring communities.

Union troubles began in Globeville in the 1890s, and in 1903, smelter workers staged a strike. Asking for an eight-hour day, the union finally ended the strike when the State of Colorado passed a law mandating the eight-hour work day.

Globeville’s most colorful figure was the leader of the smelter workers union, an Austrian immigrant named Max Malich. Dubbed by newspapers “the King of Globeville,” Malich ran a grocery store, meat market and saloon in Globeville. He was not only instrumental in the 1903 strike, but rubbed elbows with the likes of “Big Bill” Haywood, a founder of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW); Charles Moyer, president of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM); and George Pettibone, another WFM leader.

In 1907, Malich was involved in one of the most celebrated trials of the Twentieth Century, the trial of “Big Bill” Haywood for ordering the assassination of former Idaho Governer Frank Steunenberg. Defended by famed attorney Clarence Darrow, Haywood was accused of ordering the killing by confessed assassin, Harry Orchard, who also implicated Pettibone and Moyer. In his 64-page confession, much of which was reportedly dictated to him by notorious anti-union Pinkerton detective, James McParland, Orchard also leveled numerous accusations against other union figures, including Max Malich.

Left to right: George Pettibone, Bill Haywood, and Charles Moyer, outside Boise, Idaho sheriff’s office awaiting trial for murder of ex-governor Frank Steunenberg. (Library of Congress)

According to Orchard, Malich had once talked about blowing up a Globeville hotel full of non-union miners. (The hotel was never blown up.) Malich also supposedly wanted to blow up a Globeville grocery store operated by a competitor. During the trial, Malich took the stand and denied all of Orchard’s charges. He admitted that he knew Orchard, and stated that the latter wanted to kill Steunenberg for personal reasons, having to do with Orchard’s mining investments in Idaho.

Haywood and the others were cleared of all charges and Max Malich headed back to Globeville. In September of 1907, his grocery store and meat market were destroyed in a mysterious explosion in which his 19-year-old son narrowly escaped death. Malich and his family later moved to the western slope where he ran a large ranch in Montrose County.

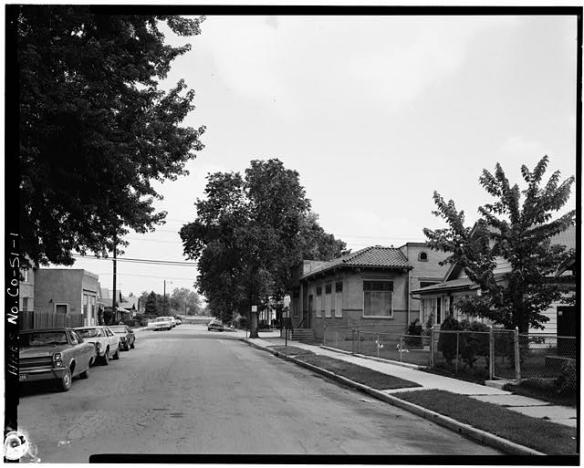

One charming historical spot in Globeville is the beautiful old St. Joseph Polish Catholic Church, located in the shadow of I-70 on Pennsylvania Street and E 46th Avenue. Another notable landmark is the 150-year-old ASARCO Globe Smelter at E 51st and Washington Street, which closed in 2006. This sprawling complex of abandoned buildings is a proposed Superfund site.

![]()

Check out my novel, THE TROUBLE WITH HEATHER HOLLOWAY, available on amazon kindle or on any device using the amazon kindle app.

Check out my novel, THE TROUBLE WITH HEATHER HOLLOWAY, available on amazon kindle or on any device using the amazon kindle app.

Her first week on the job, and Marshal Beth Mayo is hit with a sex assault case. It’s a nasty shock for the bucolic mountain town of Sugarloaf and for Mayo, who is still recovering from her husband’s death. Her initial skepticism grows into disbelief over the victim’s zany story, and she dismisses the case as a false report. Unfortunately, the same woman is soon discovered in the ruins of a ghost town, most definitely murdered.

Mayo unravels the complex case through a parade of colorful suspects and misfit family members, all the while following a common thread from 150 years earlier — Colorado history’s most notorious event, the Sand Creek Massacre.

Thank you for that bit of history. I am interested, because I am a descendent of Max Malich!

You’re welcome! What a fascinating ancestor.

Do you know where I could find a picture of the house at 4931 Pearl St which

was tore down in the late 70’s

Hi Dean, You could try History Colorado in Denver or the Denver Public Library photography collection.

Thank you so much.

The Mill and Smeltermen’s Union lost their battle in 1903 – the Grant Smelter closed, eliminating 400 or so jobs. Nor did workers achieve an eight hour work day – only bitterness remained. For information on the history of the smelting industry in Colorado and read James E. Fell’s “Ores to Metals, The Rocky Mountain Smelting Industry,” University of Nebraska Press. The book is a good read and contains detailed accounts of labor wars.